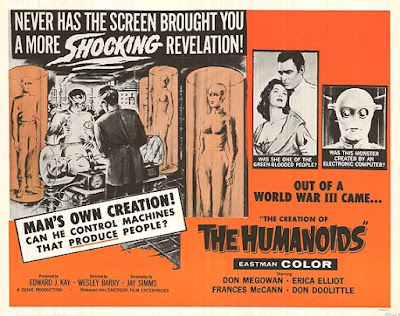

This

eighty-four-minute American science fiction double feature was

directed by Wesley Barry for Genie Productions Inc. and released by

Emerson Film Enterprises. Who knew? The Eastman color is rich and

dense with cinematography work by Hal Mohr enhancing the simplistic

and colorful set designs—highly interpretive as if for a modern

stage play. But Shakespeare this is not. Most of the lowly budget was

spent on paper to print the massive scripts that rival Congress's

pork projects. Jay Simms created the most talkative film of the

Sixties. Through its knee-deep dialogue, it attempts to convince the

viewer that humans and humanoids share many similarities. This film

is a real technical head-scratcher, so it is pointless to divulge any

of its fictitious jargon.

From

the pessimistic Hollywood playbook comes the story that most of

humanity has been destroyed by a nuclear war. Humanoids are an

advanced type of robot that work closely with humans. They are

created from man's unique ability to learn, his memory, his

personality, and his philosophy. The uppity “oids” seem a wee bit

condescending. Today, they may visually remind one of the future

Ernst Blofeld, played by Donald Pleasence, in You Only Live

Twice. Like Blofeld, they dress in “Communist” uniforms with

their banded collars. These Godless humanoids routinely recharge at

stations they call "temples" and exchange information with

a central computer known devotedly as "the father-mother." Their glowing

eyes are creepily well done.

"The

Order of Flesh and Blood" is obviously the humans. They are

constantly assessing the humanoids whom they fear are planning to

take over the world. They do seem to be quick learners. One local OFB

union leader is played by the towering Dan Megowan, who may be the

only familiar face in the film due to his many television western

roles. There is a love interest, of sorts, which becomes a real

eye-opener for him. The wardrobe for all OFB members are sleek “Bob

Mackie” versions of a Confederate soldier's uniform of powder blue

shirts combined with a reflective material topped off by a period

“Rebel” cap. Jazz hands! Certainly non-issue during the Civil

War.

Note: The

film suggests humans should not judge humanoids too harshly. Their

words might come back to haunt them. Increasingly, humans have

difficulty recognizing themselves. A sly, thought-provoking ending

comment by the film's research doctor intimates that identity is

deeper than mere appearance.