April 26, 2021

STARK FEAR (1962)

April 19, 2021

LOOPHOLE (1954)

At about the forty-five-minute mark, things start to rev up for Sullivan, now a taxi driver. His next fare is an irate Hughes with sugar daddy Beddoe. How this age-disparate couple ever got together might be worth a sub-plot. While taking a call from dispatch outside the cab, they recognize Sullivan's photo ID and hightail it. Sullivan suddenly recalls the fare’s voice. It is the first of too many contrived close calls.

The film ends with a “travelogue-style” voice-over as we see Sullivan, now an assistant bank manager, welcoming Haggerty. Outside, peering in, stands granite-faced McGraw, still on “The Sullivan Case.” They both laugh, knowing he has lost all credibility.

Note: Burly Richard Reeves has a couple of good turns as the taxi business owner. The best is nearer the end at the apartment of Beddoe. Sullivan asked for Reeves’s help and to meet him there. The ever-present McGraw arrives there first, however, after the “Hughes-Beddoe Gang” escapes. He finds Sullivan waking from a knock on the head. When Reeves and his taxi pal show up, they stop McGraw from pounding on Sullivan, not letting him leave the room to pursue him. Reeves insists. One solid punch and McGraw turns all limp. “Keep forgettin’ my own strength,” he confesses.

April 12, 2021

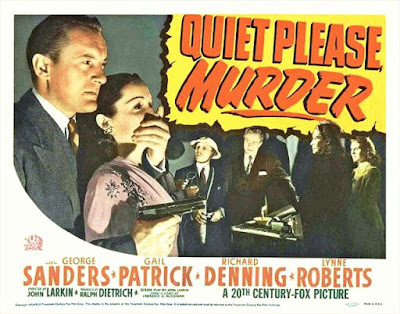

QUIET PLEASE, MURDER (1942)

April 5, 2021

FORGOTTEN FILMS: TV TRANSITION

Character actor Harry Lauter seemed destined for television. His many uncredited film roles began a career in which he was better known as “what’s his name” or “that guy.” Though the western villain made up a big chunk of his career, he had bit parts in modern settings like White Heat (1949) or a radio officer in Twelve O’Clock High (1949). He received billing for a small role in Experiment Alcatraz (1950), as a wheelchair-bound veteran. Lauter had uncredited roles in the film noir Roadblock (1951) and as a platoon leader in The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951). He was also uncredited in two notable crime films, Crime Wave (1953) and The Big Heat (1953). His network appearances on the small screen eased him away from the uncredited roles. But never entirely.

Lauter kept busy with several appearances on The Lone Ranger (1949), The Range Rider (1951) and The Adventures of Kit Carson (1951). Lauter guest-starred in one of the twenty-six episodes of Biff Baker, U.S.A. (1952). He played Atlasander on eleven episodes of the serial, Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954). He neared stardom in Tales of the Texas Rangers (1955) playing Ranger Clay Morgan for three seasons. Part of the popularity was its twist on the typical western. Each week Willard Parker, as Ranger Jace Pearson, and Lauter played Rangers from different points in history.

Lauter certainly hit his stride on many popular shows during the Fifties. When he was not riding horseback, one might find him in such comedies as The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet or My Favorite Martian. Strictly as a straight man of course. As the Sixties came to a close, Lauter made several appearances on Gunsmoke and Death Valley Days during the western’s waning years. The Seventies cast him often as a sheriff or detective. However, small the role he was a dependable actor.

Note: Before retiring in 1979, there was the occasional bit part in a few forgettable films but television is where he made a name for himself as Harry...somebody or other. He devoted much of his energy late in life to his own painting and running an art gallery.